Why Amtrak can't just build more rail

Passenger rail is in a pretty rough state in the U.S. and it's unlikely to get better anytime soon

Europe’s passenger rail system carries millions of travelers daily. China built a national high-speed rail network in just 15 years, connecting all its major cities. India is rolling out its own national high-speed rail system as you read this newsletter. But the United States? Almost nothing has been done with our passenger rail network over the last few decades. There have been minor improvements and upgrades, sure, but when compared with any of these other three regions of the world? It may as well be nothing. So why hasn’t Amtrak been able to grow and expand its footprint when far less wealthy countries have? Well, it all starts with the country’s unique geography and a rail history like no other.

And, as usual, I have a super video all about this subject as well if you’d prefer to watch rather than read:

The U.S. was once a leader in rail

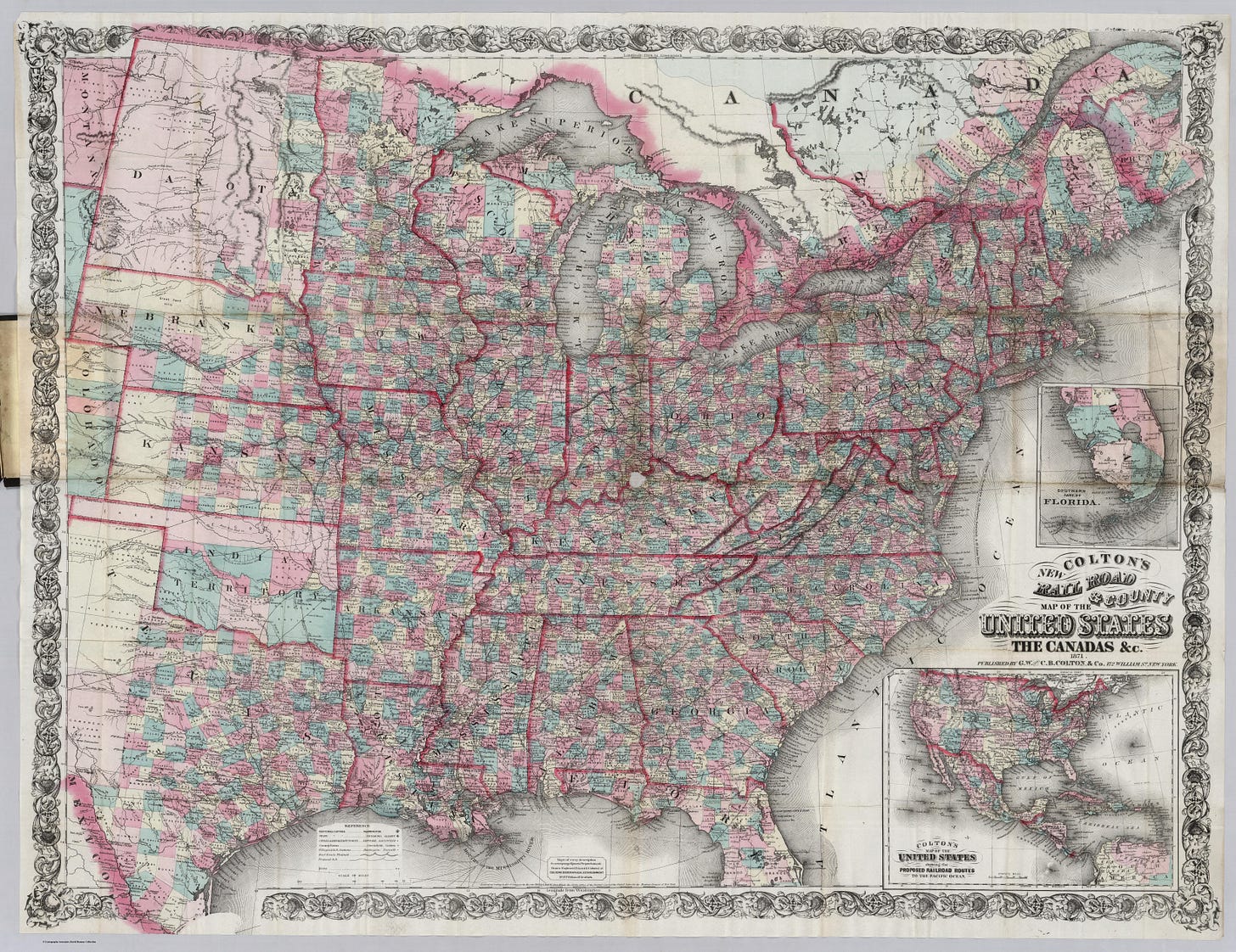

In the early years of the United States, passenger rail was the backbone of transportation and a key driver of the country’s growth. From about 1850 to 1920, the country literally raced to connect cities, towns, and rural areas by rail mostly in the hopes of pushing people westward. During this period of time, railroads offered an unprecedented level of mobility, reducing cross-country travel time from a grueling six-month journey to just a single week.

And, of course, a critical milestone in this vast rail network was the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, which linked the eastern rail network in Missouri with the western rail network, building out from San Francisco. The Northern Pacific Railway, completed in 1883, further expanded these connections, linking the Midwest to the Pacific Northwest and opening vast new territories for settlement and commerce. Unlike today, by the early 1900s, the United States had one of the most comprehensive passenger rail systems in the world and was really the envy of the modern transportation age.

But then things went sideways for rail transportation! The rise of the automobile industry and the expansion of air travel changed everything. In particular, the Interstate Highway System, built in the 1950s, made car travel far more convenient. And with a bourgening automobile industry and a level of wealth and power consolidated in the companies that ran the industry, came the means to stall or outright dismantle their primary competition at the time: passenger rail. And then, beginning in the 1950s and 1960s, government-subsidized airports and air traffic control made flying faster and cheaper. Because of this, by the 1960s, passenger railroads were losing money, and private companies began cutting routes, focusing instead on the more profitable freight business.

Side note! The United States is still very much a rail country. It’s just not a passenger rail country. Freight has completely dominated rail and much of our goods and products are moved around by rail. This would be in contrast to Europe which primarily relies on trucks, leaving most rail available for passengers. But I’m getting off topic here!

The birth and life of Amtrak

Now, despite cars and planes dominating transportation, there was an effort put forward by the federal government at the time to prevent the total collapse of passenger rail. That effort was… Amtrak! Which was formed in 1971 as a semi-public corporation which would inherit a patchwork of aging equipment and routes from formerly private companies. But there was a really big hitch in that it didn’t own most of the rail lines it operated on. Instead, these tracks remained under the control of freight companies, which prioritized cargo over passenger trains. This forced Amtrak into a system where delays and limited expansion opportunities became the norm.

While some routes, like the Northeast Corridor between Boston and Washington, D.C., remain competitive and profitable, much of Amtrak’s network serves sparsely populated areas with infrequent service. The lack of investment in passenger rail has left large swathes of the country without viable train options, a stark contrast to the golden age of American rail travel.

Today, Amtrak operates as the almost sole provider of passenger rail in the United States, managing a network that spans over 21,000 miles and connects more than 500 destinations across 46 states. But despite this reach, traveling by rail remains an afterthought for most Americans. Compare this to China’s 28,000 miles of high-speed rail or Europe’s 125,000 miles of passenger rail, and Amtrak’s shortcomings become clear.

Amtrak’s flagship service, the Acela, is its most profitable route, attracting business travelers and commuters between Washington, Philadelphia, New York City, and Boston. In 2024, nearly 3.3 million people rode the Acela. To put that in perspective, the busiest air route in the U.S. — between Atlanta and Orlando — sees about 3.5 million annual passengers. However, the Acela is the exception, not the rule. Most of Amtrak’s regional routes see fewer than 500,000 riders annually, with some attracting fewer than 100,000.

Long-distance routes like the California Zephyr and the Southwest Chief offer scenic journeys but struggle with delays and low ridership. Even Amtrak’s highest-performing long-distance route, the Silver Star between New York City and Miami, had only 388,000 riders in 2024.

To address these challenges, Amtrak has laid out its "Amtrak Connects Us" plan, which aims to expand service to 160 new communities by 2035. This includes over 30 new routes and improvements to existing ones, such as proposed corridors connecting Atlanta and Nashville, Phoenix and Tucson, and Cleveland and Columbus. Additionally, infrastructure projects like the Gateway Program, which seeks to modernize rail connections between New Jersey and New York, promise to improve service reliability.

However, Amtrak still lacks true high-speed rail. The Acela tops out at 150 miles per hour, and only for a short 50-mile stretch. Compare that to Europe’s 186 mph trains, China’s 217 mph trains, and Japan’s Shinkansen at 200 mph, and Amtrak’s shortcomings are glaring. High-speed rail remains a long-term goal, but progress has been slow. In the meantime, Amtrak is focusing on replacing its aging fleet with more efficient and environmentally friendly trains to attract new riders.

Why Amtrak can’t just build more rail

A common criticism of Amtrak is that the U.S. should be able to replicate China’s success in building a high-speed rail network. In 2008, China had just four short high-speed rail lines, none of them connected to each other. But by 2017, nearly every major city in China was linked by high-speed rail. Meanwhile, Amtrak has introduced no new routes on the tracks it fully owns. The contrast between these two passenger rail systems is stark.

Now, at first glance, the comparison between the United States and China seems fair. Both nations are geographically similar in size, with sprawling populations and growing transportation needs. But when you dig in a little deeper, the similarities end there. For example, the population density of the U.S. is just 91 people per square mile, while China’s is 390. And when factoring in where people actually live, China’s density in its rail-heavy eastern half jumps to over 600 people per square mile. By contrast, the United States, while still heavily dominant in the east, has a significant portion of its population in the western and Pacific regions of the country. Amtrak can’t just ignore those population centers in the way that China kind of can. And that brings us to our next point: the physical geography of the US is intense when you head westward.

Much to no one who reads this newsletter’s surprise, the western half of the country is dominated by the Rocky Mountains, vast deserts, and then the coastal mountain ranges. These features make constructing and maintaining rail infrastructure costly and complex.

But even in the eastern U.S., where population density is higher and the physical geography is much easier to build on, strong property rights in the U.S. complicate the process. Unlike in China, where the government can essentially just seize any land it wants for infrastructure projects, Amtrak would need to purchase land from thousands, or tens of thousands, of private owners, each with different individual interests. This often inflates costs and stalls projects indefinitely and a single property owner can bring a project to its knees.

Because of all of these issues, the future of American rail likely doesn’t lie in a single national high speed rail system but in regionally focused high-speed rail projects. Initiatives like California High-Speed Rail aim to connect the state’s major cities, while Brightline Rail in Florida and its planned Los Angeles-to-Las Vegas extension showcase the potential of privately funded rail systems. Projects like the Central Texas Railway, which aims to link Dallas and Houston, and the proposed Pacific Northwest High-Speed Rail corridor between Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver highlight the advantage of targeted, regional solutions in a country where a national build out is nigh impossible. Even Amtrak’s own Acela service in the Northeast demonstrates that concentrated, high-speed rail can succeed in densely populated regions.

All this is to say, while a coast-to-coast high-speed rail system remains a very lovely dream (I would love it anyways), these regional initiatives may be the thing that proves that rail can still play a vital role in America’s transportation future, even if its only in little chunks and completely unlike what China and Europe has.

Great Article! As an Interrail Enthusiast in Europe, the idea of not being able to travel by train is terrifying. Another thing that I find incomprehensible about America, is that, even though they have such a good highway system, nobody travels by long-distance bus routes. A concept similar to Flixbus would be an interesting thought.

Talk about all the subsidies one wants but cars win over rail because:

a) Most trips are local or regional. Point to point is more efficient.

b) Car expenses are per car, not person. If I drive 500 miles, it costs me ~$250 whether it's 1 person or 5 in the car. Air and rail, that's per person.

c) Most people don't recognize the per trip cost of that mileage on their car; they just see the $$ shelled out for the gas ( psychological, not logical ).

The biggest reason ---> The cost of driving has massively decreased.

In the 1920s and 1930s a car would maybe last ya 50,000 miles. By the 1950s and 1960s, it doubled to 100,000 miles.