What France really wanted with French Indochina

Resource extraction, of course, but there was something more

A few months ago, I wrote an article all about why Thailand was never colonized. It’s a fascinating story because if you look all around Thailand at the time, basically everywhere else was. Myanmar and Malaysia by Britain, and Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam by France. And now that I’ve been traveling through Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand (I’ll get you next time Laos!), you can see the colonial influences in both Cambodia and Vietnam and the distinct lack of colonial influences in Thailand. It’s a spectacle to behold in person.

Now, obviously, being in place somewhere means I’m naturally more interested in its geographic place in the world. I just spent a little more than 3 weeks in Vietnam, from Hanoi in the north, through Da Nang and Dalat, and all the way to Ho Chi Minh City in the south (with just a touch of the Mekong River Delta) which means it’s been pretty top of mind. One thing I noticed throughout it all is that Vietnam is BOOMING! I didn’t really expect it to be completely impoverished, but it’s certainly closer to a country like Taiwan than I would have expected. As such, I created a whole video about Vietnam’s rise as a global economic power, which you can watch if you like.

But this article is what came before Vietnam’s modern rise. This article is about France Indochina and what France wanted with all this part of Southeast Asia specifically. You might think it’s all about resource extraction, which is true of course, but it goes a bit deeper than that.

Why France wanted Southeast Asia

France’s colonization of Southeast Asia began in the mid-1800s and ultimately formed what became known as French Indochina, an French colony made up of modern-day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. But this colonial experiment wasn’t just about land or resource extraction, though both certainly played a role. It was about strategic positioning, access to global trade routes, competition with Britain, and the deeply rooted belief that France had a “civilizing” (don’t get me started on that word) mission to uplift what it saw as less developed cultures. But in trying to impose its will on Southeast Asia, France left behind a complicated (and painful) legacy that continues to shape the region to this day.

France first made inroads into Vietnam during the 1850s, using the pretense of protecting Catholic missionaries who were being persecuted by the Nguyễn Dynasty. It was this religious and humanitarian justification that helped sell the conquest back home in Paris, but the real motivations were strategic and economic. You see, France saw Vietnam as a potential gateway to China, a massive and still largely untapped market at the time. This would not only bolster its finances back home, but it would also better enable France to directly compete with Britain, its primary competition on the global colonization efforts. During this time, after all, Britain had effectively colonized Myanmar, Malaysia, India, and had made significant inroads into colonizing China by taking Macau and Hong Kong. Indochina was France’s best attempt at competing in the region.

So, in 1862, France annexed the southern region of Vietnam, known as Cochinchina. Over the next few decades, French control expanded northward, with Annam and Tonkin eventually falling under French authority as protectorates. By 1887, these three regions (Cochinchina, Annam, and Tonkin) were merged into a colonial federation along with Cambodia, and later Laos, forming the full entity of French Indochina.

As with most colonies, the French ran Indochina with a deep hierarchical structure. Indigenous rulers were retained in some places for show, but real power rested with French administrators. This economic system was built to benefit France first and foremost: roads, railways, and ports were constructed to extract resources more efficiently. Local farmers were taxed heavily and often forced into labor or low-wage jobs on rubber plantations. While France did introduce modern education, it was primarily designed to create a small class of French-speaking elites who could help manage the colony, not to uplift the broader population of Vietnam, Laos or Cambodia. In fact, during this time most Southeast Asians under French rule remained impoverished, disenfranchised, and excluded from any real say in how they were governed.

Because of this, Vietnam became a hotbed of resistance. Nationalist and communist movements began to grow during the early 1900s, and became much more prominent under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh, who would later lead North Vietnam in the war against both France and the United States. Cambodia and Laos also had their own independence movements, though they were more fragmented and less successful. But World War II would change everything. Not just for Indochina but certainly in Indochina as well.

Ultimately, World War II exposed the fragility of colonial control. When Japan took over and occupied the region, expelling the French in the process, it undermined France’s authority and gave local independence leaders a taste of self-rule. It also showed that European colonizers were not invincible as they might have appeared prior. Japan proved that Asian countries could match and beat European powers. So why couldn’t Vietnam?

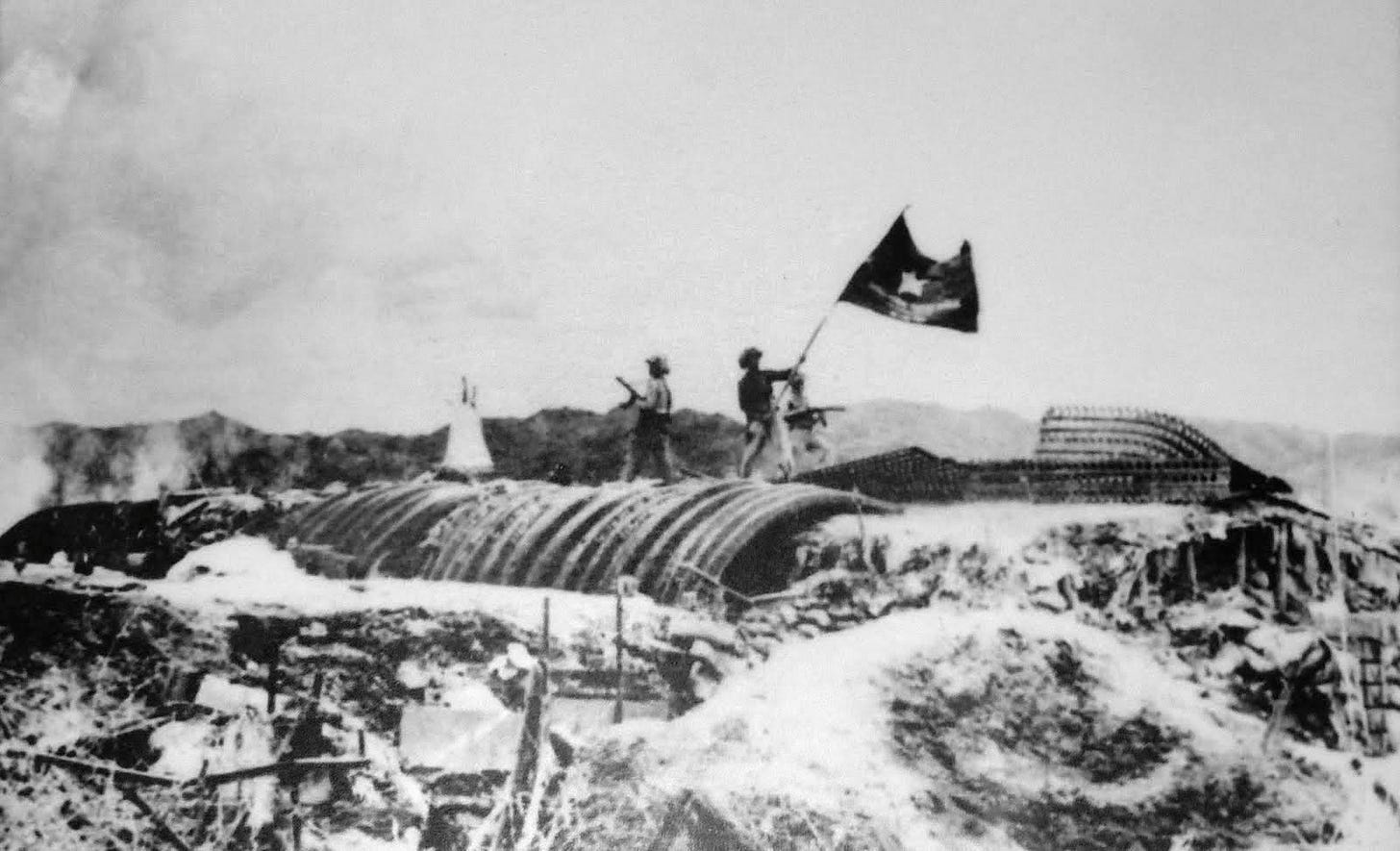

After the war ended, Indochina was “returned” to France and the French attempted to reassert its dominance as if nothing had changed. But things had changed! The entire region, but especially Vietnam, no longer saw France as a power it couldn’t fight off. This led to the First Indochina War, which France ultimately lost in 1954 after the pivotal battle of Dien Bien Phu. It was this exact battle that showed that Vietnam could match the tactics and military superiority of Europe. France, at the time, wrongfully assumed that Vietnam had no anti-aircraft capabilities, which turned out not to be true and disastrous for the French forces.

The legacy of French Indochina is still felt today. Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia each bear marks of their colonial past. French architecture, language influence, and educational systems linger, especially in urban centers like Hanoi, Phnom Penh, and Vientiane. Even cuisine was largely changed. Banh mi sandwiches, after all, are a direct result of France’s colonization. But so too does the trauma of colonization such as political instability, rigid class divides, and a lingering sense of national identity forged in opposition to foreign rule. In Vietnam, in particular, the anti-colonial struggle eventually morphed into a broader Cold War conflict with the United States. In Cambodia and Laos, years of civil war and foreign intervention followed independence.

France, for its part, has had to reckon with its colonial legacy in fits and starts. The wars in Indochina were not just military defeats, they were moral and ideological ones that shook the foundation of French imperial ambition. And while modern France often celebrates its language and culture abroad, the legacy of colonialism in Southeast Asia is more complicated.

The French language wasn't as entrenched in Indochina as in various other French colonies, like Lebanon or Algeria. Thus, unlike in those other colonies, in Indochina French was spoken by and large exclusively by the elites and so forth.

This is meaningful since I am old enough to have been affected by the war. Personally told then President Richard Nixon to get out of the war and he ignored me. Action Kid from NYC has recently done walking tours of Hanoi and Ho Chi Min City and I am shocked by how modern they look. They are posted on YouTube, he is there now.