A question as old as time itself. That’s actually not true. The very idea of continents wasn’t even a thing until ancient Greece came around and determined there was a difference between Europe and Asia. Those ancient Grecians really did know how to think up new ideas about the world, didn’t they? Regardless, today we have sorted out our global land masses into geographically distinct continents. Most people recognize that we have continents (I won’t say everyone because … *waves around generally*). But how we organize, partition, and separate those continents is very much up for debate.

And, of course, we now have an 8th continent as well which, if you’re interested, you can check out in my newest video this week:

All of this leads to a question though: how many continents do we actually have? Leaving out Zealandia, the answer is more nuanced that you might think and largely depends on where you’re from.

So what exactly is a continent?

At its core (get it? 😅), a continent is a very large landmass separated from other landmasses by water or extensive mountain ranges. This is, of course, a simple definition, but it quickly expands to include several key characteristics that distinguish a continent from something like an island or just a large piece of land.

Firstly, a continent is defined by its tectonic plate. Continents typically sit atop their own distinct tectonic plates, or at least a significant portion of a plate, which drift over the Earth's molten mantle. This geologic foundation means that continents are not static! They have (and will continue to) move, collide, and separate over millions of years, shaping and reshaping the Earth's surface. For example, the African Plate, the North American Plate, and the Eurasian Plate are distinct entities that largely correspond to their respective continents. But if we just went with tectonic boundaries then we’d also end up with things that don’t quite make sense, such as India being continent-less.

So, secondly, a continent must also possess a significant and connected land area. While there's no universally agreed-upon minimum size, continents are undeniably vast. They contain a wide range of geographic features, from towering mountain ranges and sprawling deserts to extensive river systems and vast plains. This large size allows for diverse ecosystems and climates within a single continental body. In this case, India is directly connected to the rest of Asia, therefore it’s broadly considered to be part of the Asian continent despite being on a different tectonic plate. This is where the whole “sub-continent” terminology comes in as well, but we’re going to bypass that for this article.

Thirdly, continents are characterized by their distinct boundaries. These boundaries are often oceanic, with vast stretches of water separating one continent from another. However, as in the case of Europe and Asia, the boundary can be a land connection as well, typically marked by mountain ranges like the Urals or by major waterways like the Bosphorus Strait. Even when land-connected, a continent maintains a geographic and often cultural cohesiveness that sets it apart. That’s a key term right there so hang on to this thought until the next section.

Finally, the concept of a continent also encompasses its continental shelf (this is where Zealandia comes in but watch the video above cause I’m not going to mention it again). This is the submerged landmass that extends from a continent's coastline into the ocean, before dropping off sharply into the deep ocean floor. While underwater, the continental shelf is geologically part of the continent and contains similar elements and crust thickness as its above-sea land.

So now that we know, broadly, what a continent is, how many are there?

Counting continents

Shockingly, because we all agree on so much these days, the number of continents on Earth is not a universally agreed-upon figure. In fact, the number can vary significantly depending on the geographic model adopted by different regions and educational systems. This divergence in belief often stems from how landmasses that are physically connected, or were historically connected, are categorized.

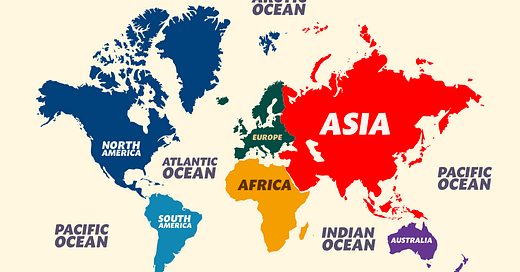

One common model, the model I was raised with which is particularly prevalent in North America, identifies seven continents: North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, and Antarctica. In this model, North and South America are considered distinct continents, separated at the Isthmus of Panama, a narrow land bridge that nonetheless provides a clear geographic division. Europe and Asia, though physically connected by land, are often treated as separate continents due to their distinct cultural and historical identities, with the traditional boundary running through the Ural Mountains and the Caucasus region (Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan get weird though…). Australia is recognized as a continent rather than merely a large island due to its considerable size and position on its own tectonic plate.

As geographers though, we rarely actually refer to an “Australia Continent” but rather use the more inclusive Oceania label to include Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, and all of the many, many disparate and far-flung islands of Polynesia, Micronesia, and the Pacific at large. But for this article, as a way of being taught, Australia is included.

Moving on, a slightly different perspective, often taught in parts of Europe, Latin America, and some other regions, recognizes only six continents. Within this model, the Americas are frequently combined into a single continent known simply as "America." The rationale here is often based on the continuous landmass from the Arctic to Cape Horn, viewing the Isthmus of Panama as a connecting point rather than a dividing line. This "America" concept emphasizes the shared geological history of the two landmasses. Odd though that some in Europe might recognize North and South America as a single continent because they’re connected but then still consider Europe, Asia and Africa as separate continents. 🤔

Which leads us to: another six-continent model! Common in Russia and some parts of Eastern Europe, this model combines Europe and Asia into a single supercontinent called "Eurasia." This approach highlights the continuous landmass that stretches from the Atlantic to the Pacific, emphasizing the geologic unity of the Eurasian tectonic plate. While culturally diverse, this model prioritizes the physical connection of the land and the tectonic forces underneath.

And then, of course, you can simple combine the last two models to create a 5-continent model: Americas, Eurasia, Africa, Australia and Antarctica. But then, why stop there? We could bring it down to four and say that any large landmass that’s continuously connected is a continent. In which case we’d have the Americas, Afro-Eurasia, Australia, and Antarctica.

Furthermore, another five-continent model is also sometimes seen, particularly in older texts or in the context of the Olympic rings, which historically represented the inhabited continents: Africa, America, Asia, Europe, and Oceania (excluding Antarctica due to its lack of permanent human habitation). This model is less about geologic or geographic rigidity and more about human presence.

Ultimately though, whether America is one continent or two, or whether Europe and Asia should be combined, comes down to the framework through which one views the Earth's grand landmasses. Each model has its own logic, rooted in a combination of geological understanding, historical perspectives, and cultural traditions that have shaped how we draw the lines on our mental, and physical, maps of the world. So to answer the question of this article:

How many continents are there in the world?

It depends on who you ask!

Why isn’t Greenland considered a continent?

Why isn’t India considered its own continent? It is more isolated from Asia than Europe is.